Sepia Saturday 807. Seventh in a series about 1943 letters from my dad’s brother Frederic Mason Charboneau during his second year of WWII US Army service.

The year 1943 was a landmark in my paternal Uncle Fred’s correspondence as he was finally able to tell family and friends back home where he had been deployed since leaving the U.S.

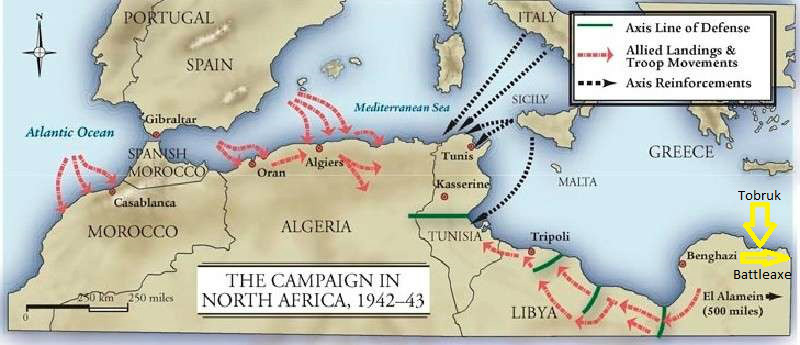

More than 100,000 U.S. troops landed in North Africa on Nov. 8, 1942, in a campaign called Operation Torch — having sailed there from the U.K. Among them was Uncle Fred’s HQ Battery of the Separate 431st Antiaircraft Battalion, Coast Artillery Corps.

Their correspondence was subject to censorship, which Uncle Fred refers to in some of his letters. However, on May 13, 1943, WWII battles ended in North Africa, and censorship was lifted for U.S. service members stationed there.

In an undated letter, written around that time, Uncle Fred was at last able to describe some of his previously embargoed experiences. The letter is typed and not addressed to anyone, so it is possible he sent it to multiple recipients back home.

“North Africa: Now that the war here in North Africa is over, I am able to give you some idea as to what we have done since landing on these African shores,” he began.

Landing at Oran

“We landed in Oran and, after a 12-mile torturous hike, we camped in a small clearing near the center of the city,” Fred continued. “We did not bother to pitch our tents as our stay was only for the night. It was beginning to get dark when we had chow and just as we were about to roll in our blankets for a much-needed night’s rest, we heard the sound of planes overhead.

“Before we had a chance to spot them, bombs began to drop. At the same moment, the whole harbor seemed to glow like an elaborate 4th of July fireworks from the fire of our Antiaircraft guns. As it turned out, the bombs from the enemy planes landed in the harbor and did no harm.”

By rail to Nouvion

After that, Uncle Fred’s unit was moved again, this time in rail cars left over from WWI.

“The following morning, we hiked to the railroad station not far distant and much to our surprise saw that we were about to board some 40 and 8 (forty men or eight horses) railroad cars from the last World War,” he wrote. “The train moved very slow, but we arrived at our destination after 1/2 day’s travel.

“The name of the town was Nouvion, which was nothing but a few scattered stone houses,” Fred continued. “We bivouacked or camped in an open field. The next several days proved uneventful, and then the rains came.“

Heavy rains and the move to Arzew

Having grown up close to nature in New York’s Adirondack region, it’s no surprise that Uncle Fred painted a vivid picture of the weather and its impact on the troops.

“The next day it started to rain quite heavily, and the field began to look like a mud mire. On the following morning, we looked out of our rain-soaked tents to see about 6 inches of mud and water surrounding our new homes,” Fred wrote. “Everything was flooded out, and we were unable to get set up stoves for a day or two for cooking any food.”

“We stayed at the field for about a month or so,” he continued, “and then loaded all our supplies and equipment onto our trucks and moved about 25 miles to the small town on the Mediterranean called Arzew [northeast of Oran]. Which incidentally was the same place that part of our outfit had come in on ….”

Reading about these troop landings and military movements, I couldn’t help but wonder what the local population made of having armies from the global north roving about their homeland — and not for the first time. Uncle Fred gives us a glimpse as his saga continues.

Next month, “Part 2: Where Uncle Fred served during 1942-43.” Meanwhile, please visit the other intrepid bloggers over at Sepia Saturday.

© 2026 Molly Charboneau. All rights reserved.